Teaching:TUW - UE InfoVis WS 2010/11 - Gruppe 03 - Aufgabe 2: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

[[Image:UE-InfoVis1011_0508080img_exp1_1.gif | 300px | thumb | alt=|''Fig. 2: Example stimuli from the aspect ratio study'']] | [[Image:UE-InfoVis1011_0508080img_exp1_1.gif | 300px | thumb | alt=|''Fig. 2: Example stimuli from the aspect ratio study'']] | ||

They conducted a series of controlled experiments to explore their hypothesis: <br/> | They conducted a series of controlled experiments to explore their hypothesis: <br/> | ||

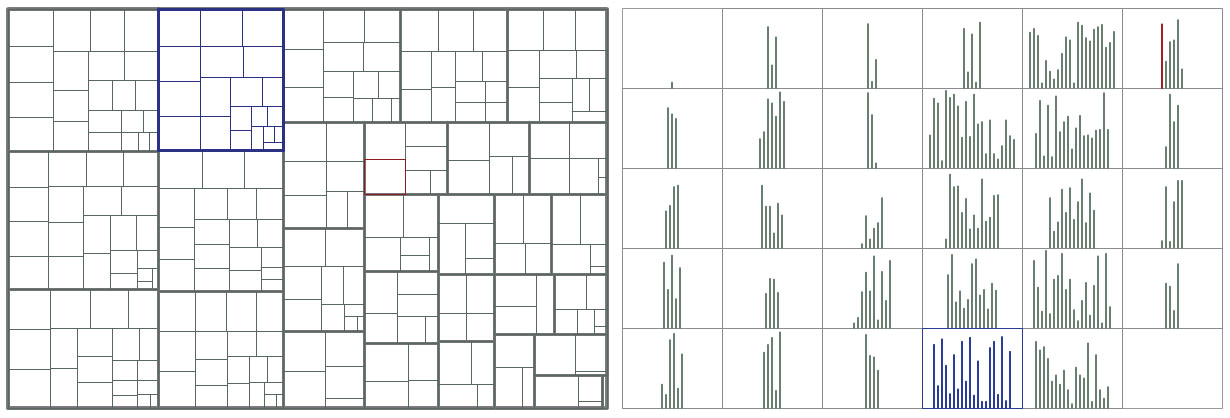

Kong, Heer & Agrawala asked | Kong, Heer & Agrawala asked participants to compare rectangular areas with varying size and aspect ratios. For this purpose they showed subjects images (Fig. 2) containing two rectangles (A or B) and asked them to identify which is the smaller one. Further they had to guess the percentage the smaller was of the larger rectangle. | ||

====3.2. Results==== | ====3.2. Results==== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

*: The highest error occurred comparing two extreme aspect ratios or squares. | *: The highest error occurred comparing two extreme aspect ratios or squares. | ||

====3.3. | ====3.3. Discussion==== | ||

Their results support the general intuition against using treemaps using rectangles with extreme aspect ratios.<br/> | Their results support the general intuition against using treemaps using rectangles with extreme aspect ratios.<br/> | ||

"''It instead seems that squarified algorithms are effective in part because (a) they avoid extreme aspect ratios and (b) in most cases they are unable to perfectly achieve their “squarification” objective, instead producing a distribution of aspect ratios.''" [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010] | "''It instead seems that squarified algorithms are effective in part because (a) they avoid extreme aspect ratios and (b) in most cases they are unable to perfectly achieve their “squarification” objective, instead producing a distribution of aspect ratios.''" [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010] | ||

===4. Experiment #2: The Effects of Data Density=== | |||

{|border="0" | |||

|The second experiment was designed to examine the data density at which treemaps become more effective than bar charts for comparing quantitative values. Kong, Heer & Agrawala chose to focus on value comparison tasks, which they believe to be the most common perceptual task performed with treemaps. [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010] | |||

<br/> | |||

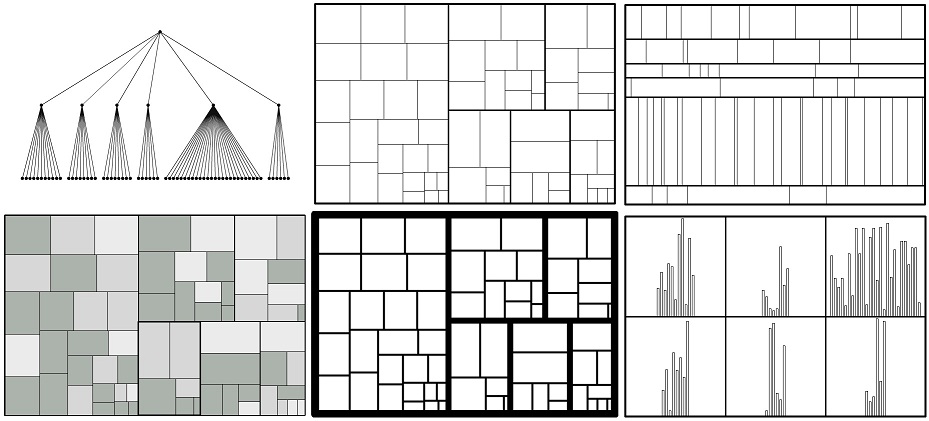

A layout algorithm was designed which uses bar charts to encode the values of leaf nodes. Figure 3 shows an example of a treemap and their hierarchical bar chart, each encoding the same data. | |||

| [[Image:UE-InfoVis1011_0508080img_exp2_1.jpg | 300px | thumb | alt=|''Fig. 3: Example stimuli from the second study'']] | |||

|} | |||

They presented participants with either a treemap or a hierarchical bar chart and asked them to compare two elements. They were asked either to compare leaf to leaf (LL), leaf to non-leaf (LN) or non-leaf to non-leaf (NN). | |||

* With a treemap, participants were asked to compare two rectangular areas. | |||

* With a hierarchical bar chart, participants were asked either to compare two bars (LL), or to compare groups of bars to one another (LN or NN). | |||

====4.1. Method==== | |||

====4.2. Results==== | |||

====4.3. Discussion==== | |||

Revision as of 01:09, 17 November 2010

Perceptual Guidelines for Creating Rectangular Treemaps

Abstract

The following Article is a summary of the work of Nicholas Kong, Jeffrey Heer, and Maneesh Agrawala [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010]. It discusses the advantages and disadvantages of treemaps as visualization tool.

1. Treemaps - Basics

Treemaps are used for space efficient visualizing large, hierarchical datasets. Therefore every node in a tree is represented by a rectangular area in the treemap, where the size is proportional to the value of the node. The hierarchy of the tree is encoded by recursively subdividing the parent areas in the treemap. Following parameters have to be configured carefully to design perceptually effective treemaps:

- aspect ratio of rectangles (affected by the chosen layout algorithm)

- luminance of rectangles (used to encode additional variables)

- thickness of borders (used to encode hierarchy)

The problem with using treemaps is the use of area for encoding data. Studies have shown that people generally underestimate area, which leads to more inaccurate decoding than with other visualization types, like bar charts. Bar charts, on the other hand, are less space-efficient, not useful for visualization of hierarchies with more than two levels, and more difficult to read at higher data densities. The underlying work gives a design guideline, based on three experiments, when to use treemaps and when to use other visual encodings and how to choose the parameters.

2. Pilot Study – True Percentage and Luminance

The authors first conducted a pilot study on true percentage and luminance to prove prior studies. The term true percentage means the physical difference of two values measured in percent. Following results could be gained:

- true percentage has a strong effect on judgment accuracy

- More accurate judgment at either small (5%) or high (95%) percentage, more accurate judgment at multiples of 5 (due to our behavior to specify numbers at factors of 5)

- luminance has no significant effects on judgment accuracy

- Because area and luminance are separable perceptual dimensions, luminance does not interfere with area judgment.

3. Experiment #1: The Effects of Aspect Ratio

The first experiment presented by Kong et al. [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010] assessed both the effects of aspect ratio on rectangular area judgments and the effects of aspect ratio on proportional judgments.

They further hypothesized three things:

- extreme aspect ratios hamper judgment accuracy

- squares would hinder judgment accuracy

- different primary orientation would increase the error rate

3.1. Method

They conducted a series of controlled experiments to explore their hypothesis:

Kong, Heer & Agrawala asked participants to compare rectangular areas with varying size and aspect ratios. For this purpose they showed subjects images (Fig. 2) containing two rectangles (A or B) and asked them to identify which is the smaller one. Further they had to guess the percentage the smaller was of the larger rectangle.

3.2. Results

They collected 2,600 responses to analyze:

- No effects of orientation on judgment accuracy were found.

- They did find a significant interaction effect between orientation and aspect ratio.

- Average judgment accuracy improves when comparing rectangles with varied aspect ratios.

- The highest error occurred comparing two extreme aspect ratios or squares.

3.3. Discussion

Their results support the general intuition against using treemaps using rectangles with extreme aspect ratios.

"It instead seems that squarified algorithms are effective in part because (a) they avoid extreme aspect ratios and (b) in most cases they are unable to perfectly achieve their “squarification” objective, instead producing a distribution of aspect ratios." [Nicholas Kong et al., 2010]

4. Experiment #2: The Effects of Data Density

They presented participants with either a treemap or a hierarchical bar chart and asked them to compare two elements. They were asked either to compare leaf to leaf (LL), leaf to non-leaf (LN) or non-leaf to non-leaf (NN).

- With a treemap, participants were asked to compare two rectangular areas.

- With a hierarchical bar chart, participants were asked either to compare two bars (LL), or to compare groups of bars to one another (LN or NN).

4.1. Method

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

TODO

... ... ... ...

6. References

[Nicholas Kong et al., 2010] Nicholas Kong, Jeffrey Heer, Maneesh Agrawala. Perceptual Guidelines for Creating Rectangular Treemaps. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and computer Graphics, 16(6):990-998, November/December 2010.